In the seven years between 1960 and 1967 Jean-Luc Godard directed 15 feature-length films, with each one of them considered to be a masterpiece by consensus. It’s an achievement that will no doubt forever linger as one of the great achievements of the cinema, as a sign of an artist captured by the spark of passion and ingenuity with which to push the medium forward.

Breathless – In Godard’s debut feature the Nouvelle Vague cemented the intent teased by Francois Truffaut’s The 400 Blows, and affirmed a sea change for the French cinema. The tale of love on the run pausing for breathe, as a hood hides out with his American [beau] in Paris, Godard’s film is loosely inspired by the story of Michel Portail, a minor celebrity terriblé that filled the gossip pages of Paris in the late 1950s. This looseness of inspiration would endemic of the director’s liberal approach to adaptation, with Breathless‘ own 1975 “sequel” Numéro Deux possibly the most explicit example of the filmmaker’s abstract intensions.

Le Petit Soldat – Often mistaken for a later piece of work, having been banned upon completion in 1960 only to be released in 1963, Le Petit Soldat explores the relationship between France and Algeria at the turn of the 1960s. The film’s protagonist, Bruno Forestier (Michel Subor) has fled France in an attempt to avoid being drafted in to the army during the Algerian war, only to find himself at the centre of a plot to assassinate a key associate of the National Liberation Front of Algeria. The already controversial subject matter is only strengthened by a third act meditation on the use of torture to garner intelligence. The famous Godardian phrase “Photography is truth, and cinema is truth 24 times per second” was coined in Le Petit Soldat.

A Woman Is A Woman – Godard’s musical, albeit one sans diegetic musical numbers, A Woman Is A Woman is as much an admission of love to the golden age of Hollywood as it is the female form itself. Godard’s second feature-length collaboration with Anna Karina (after Le Petit Soldat), the woman who, alongside Hollywood itself, was perhaps the director’s greatest influence during this period of his work. Karina stars alongside Jean-Claude Brialy, who features in one of the director’s early shorts, All The Boys Are Called Patrick, and Breathless‘ Jean-Paul Belmondo, in the tale of a woman torn between two men; her boyfriend and his friend. The film was shot in Francoscope, a knock-off/variation on CinemaScope, and marks Godard’s first time working in colour.

Vivre Sa Vie – Subtitled “A Film In 12 Scenes“, Vivre Sa Vie charts the downward spiral of an ordinary young women who falls in to a life of prostitution. It opens with one of the most interesting sequences in Godard’s career, as the director has his protagonists literally turn their backs to his audience, as a long discussion takes place in as alienating and abstract a manner as is possible. The alienation continues throughout, with the vérité stylings that had infected the narrative cinema of the neo-realists and the arthouse Japanese cinema of the time a clear influence, as the film’s central character Nana (Karina, for the third time in successive films) is shot from afar, to be walking the streets as if filmed by a dislocated newsreel cameraman. Once again the cinema features heavily, as Nana seeks solace in the movie-house, and a screening of Carl Th. Dreyer’s The Passion Of Joan Of Arc, the events of which mirror both the plight of Godard’s character and the director himself. He treated Vivre Sa Vie as a cathartic experience, as a means of dealing with his own relationship anxieties stating in his own words that “I was preoccupied by my problems with women. I found that the cinema could expose the shame without embarrassment”.

Les Carabiniers – A film about the horrors of war, Les Carabiniers was a marked failure for the filmmaker, with it’s existential take on the typical ultimately rather ahead of it’s time. And quite literally too, at least within the context of Godard’s own oeuvre. While the film itself remains a curio, it’s influence over the second part of the filmmaker’s career is readily apparent. Notably, Les Carabiniers is the only film compiled within this list not to be shot by Raoul Coutard.

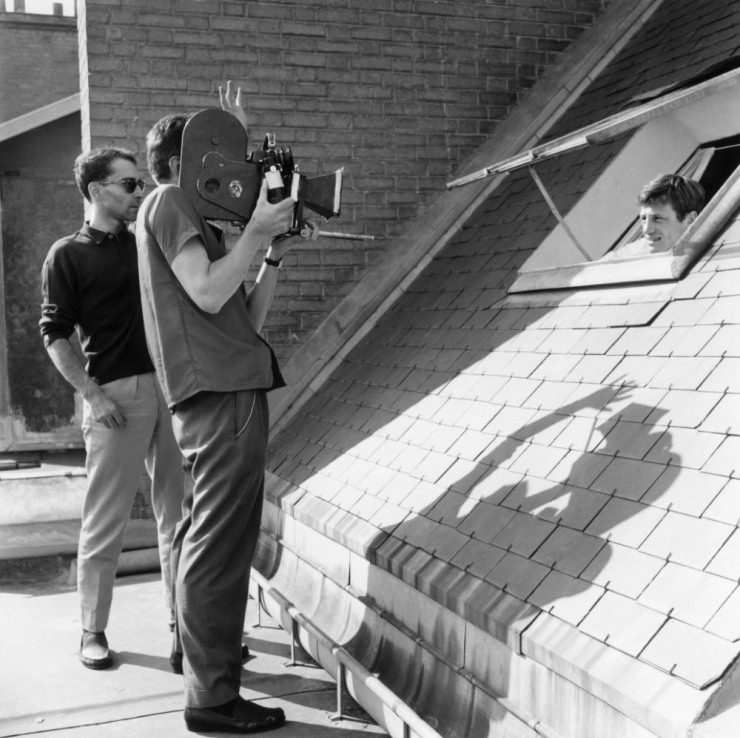

Le Mépris – His most blatant celebration of the movies, and one of the great films about film. Le Mépris explores the relationship between creative and moneyman, in this story of a filmmaker (Fritz Lang, as himself) working on a European project backed by an American producer (Jack Palance) and the writer (Michel Piccoli) who stands between them. And his wife (Brigitte Bardot). The presence of Bardot is a clear nod to the Roger Vadim films (And God Created Woman, Les bijoutiers du clair de lune) that alongside the films of Louis Malle and Jean-Pierre Melville paved the way towards the Nouvelle Vague, while the Franco, American, German triptych that forms the centre of the piece is a neat analogy for the manner in which the three countries had tussled for cinematic dominance since the end of the First World War.

Bande á Part – The film which was perhaps the closest in tone, both stylistically and in the way in which it paid homage to popular culture and cinema to Breathless, Bande á Part, aka Band Of Outsiders might just be Godard’s most mainstream work from the period. A three party love affair once again takes precedence (as per most of the director’s films of this period), with the relationship surrounding a heist story that results in one of the most memorable shoot-outs in all of the cinema. The film’s sign off is as typically playful as anything else from this run of films too, with the promise of a sequel shot in Technicolor made as the surviving protagonists drive off in to the sunset. It was Bande á Part which led to this misalignment of Godard with the quote “All you need to make a film is a girl and a gun”, a line which Godard himself insists was first used by D.W. Griffith.

One Pingback